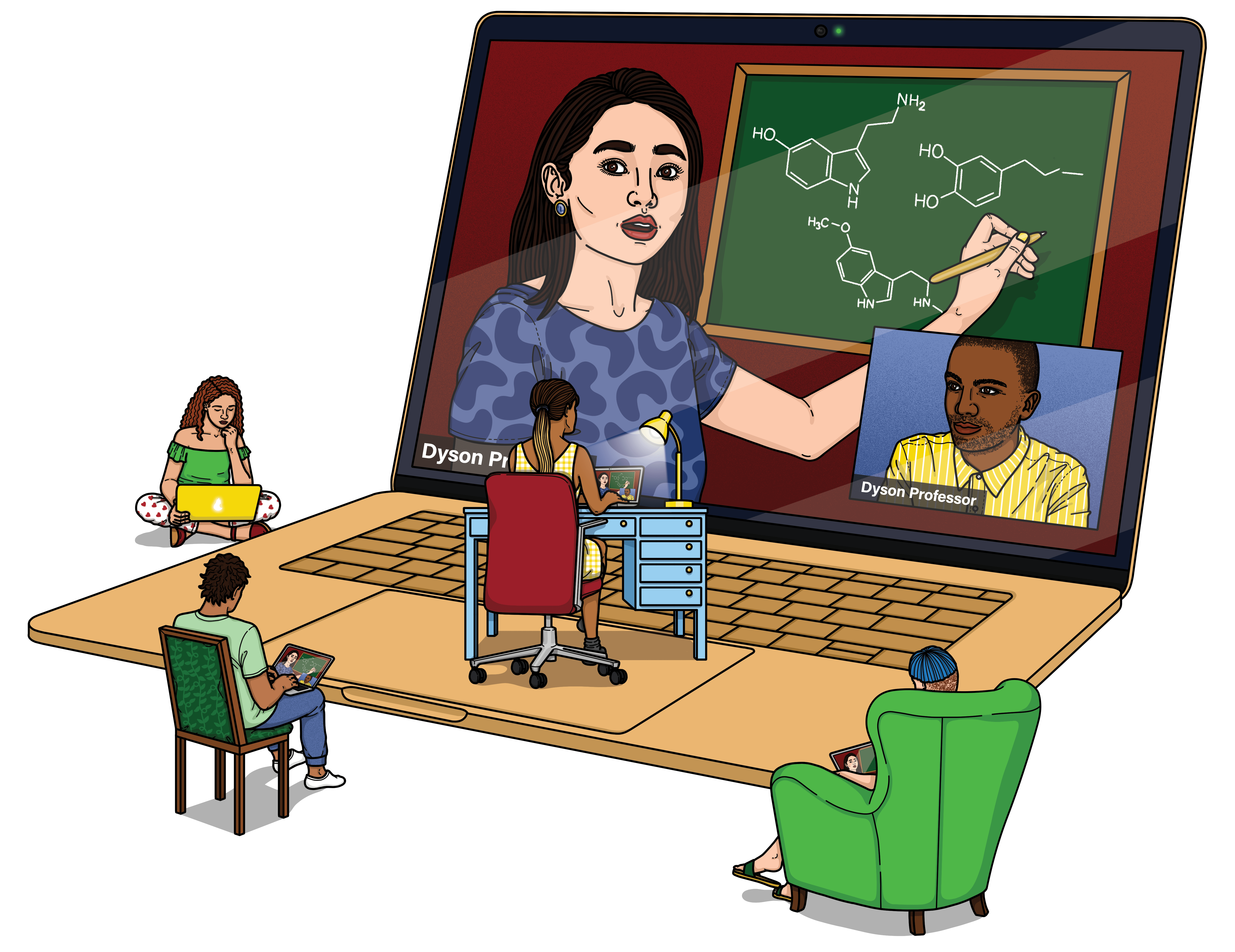

Remoting In

Dyson College has responded to the new normal.

Remoting In

Dyson College has responded to the new normal.

W hen the coronavirus pandemic hit and Pace moved to remote learning, the University community found ways to adjust.

“I am very proud of how Dyson’s students, faculty, and staff quickly adapted to the new normal of remote teaching and learning during a trying time,” Dean Nira Herrmann, Dyson College of Arts and Sciences, said. “It’s a demonstration of our students’ commitment to their education and of our faculty’s and staff’s dedication to creative solutions that work.”

How did they replicate the hands-on aspects of liberal arts learning such as science labs and performing arts classes? What about the fact that, for many students, financial concerns and upended living arrangements threatened to derail their academics? Here’s a closer look.

Academic advising

For Dyson’s team of academic advisors, providing students with the same level of service and engagement they would have received in person was paramount. To that end, leveraging technology and responding to feedback were critical. When remote learning began, advisors created automatic email replies to ensure that students quickly received important information such as upcoming deadlines or COVID-19 information. On the New York City campus, they also conducted group sessions, and a live chat was launched via the Zoom virtual conferencing platform to efficiently provide answers to quick questions. In addition, each student who participated received a satisfaction survey, which enabled advisors to monitor and refine service to best respond to student needs.

“I am very proud of the adaptability, hard work, dedication, and commitment of the advising team,” Heather Calchera, assistant dean, Student Advising said. “Our jobs can be challenging, but also very rewarding. It was a pleasure to witness our students thriving despite these stressful times.”

Art

It doesn’t get much more hands-on than a studio art class, so Eve Laramée, a professor in the art department and director of the Center for the Arts, Society and Ecology, was somewhat surprised to find that the transition to remote learning was fairly seamless. Laramée used a full range of tools including Blackboard, email, online videos, video tutorials, short films, and LinkedIn Learning, while also giving some instruction during class time and holding remote office hours at her regular schedule.

“Students submitted photographs of works in progress so I could provide ongoing feedback, and then uploaded finished works in the form of photographs to Blackboard, or emailed them to me, or both,” Laramée said. “This provided regular structure, and that helped keep things feeling ‘normal.’”

Most importantly, she remained conscious of the many challenges facing students as a result of the unexpected changes, including limited access to technology. This meant more frequent communication with those needing extra support, allowances for students who returned to homes abroad, and suggestions for alternative materials for those without their regular art supplies.

Moreover, Laramée encouraged her students to use their art as a way to de-stress and to process their reactions to the pandemic. She also modified assignments, giving students the option to address COVID-19 in their work.

“The assignments, and the students’ responses, were all about meaningfulness, because that’s what art is, creating meaning for culture and society,” Laramée said.

Biology

Professor Marcy Kelly, PhD, chair of the biology department in New York City, replaced her traditional instruction with a blend of online tasks and shorter meetings via Zoom, which included breakout time for students to meet in smaller virtual groups. Online assignments and review were organized around digital supplements to course textbooks, as well as a series of videos that she curated.

She also created a to-do list for each week and gave students options for working on group assignments. If it was not practical for them to work via Zoom, they could choose to collaborate through shared files.

“I don’t think [synchronous instruction—requiring students to meet together at a specific time for a set duration—] is a great idea,” Kelly said. “Literature suggests that doing the typical lecture style isn’t really pedagogically ideal online.”

Like Kelly, Antonio Herrera, PhD, also focused on meeting students’ diverse needs. A lecturer in the biology department on the New York City campus, he had one big objective for his lab class of mostly first-year students: “to make them feel like they just left lab,” Herrera said.

That meant finding new ways for them to work together and connect, as they normally would in person. To enable opportunities for remote interaction, Herrera also used the breakout room functionality on the Zoom platform, but instead of limiting students to working with their previous lab partners, he randomly assigned them to virtual groups. This allowed students who might not have associated in person to meet and collaborate, and Herrera said students seemed to appreciate the approach. They stayed on video conference calls and continued to work even after the session was scheduled to end, he said.

Herrera and his students also explored resources available through JoVE, the Journal of Visual Experimentation. Content made accessible during the pandemic has included highquality video of experiments and lab techniques.

“Many things that I thought were impossible to conduct remotely in a lab became a reality,” biology major Khaela Gardner ’23 said.

As much as they hoped schoolwork could provide a diversion from the stress and anxiety caused by the coronavirus, both Herrera and Kelly also engaged students by focusing on the pandemic. Kelly set up a viewing party featuring the 2011 film Contagion, by Oscar-winning director Steven Soderbergh (Traffic), and students in Herrera’s Biology and Contemporary Society lab course created an array of four COVID-19 infographics designed to clearly present information underlying several aspects of the pandemic.

“The goal was to give them the opportunity to do something about COVID-19,” Herrera said.

“It created a rewarding

opportunity for the students

and contributed to their

own wellbeing by giving

them a purpose during this

trying period.”—Reginald Flowers, Performing Arts

Communication Studies

When it comes to his students’ well-being, Melvin Williams, PhD, an assistant professor in the communication studies department, led by example.

“I called the New York COVID-19 mental health hotline, told my students about the experience, and urged them to do the same, if needed,” Williams said. “I wanted them to know that we can, and will, heal together.”

Williams, who did have previous experience teaching hybrid courses mixing face-to-face and online instruction, started by hosting a Zoom meeting to find out what his students needed and wanted out of the unexpected remote experience. Conversation included a frank discussion of students’ new normal, and he acknowledged the grief that many were feeling over the loss of those moments that define the college experience, such as senior year memories, honor society inductions, and social gatherings.

In providing remote coursework, including recorded lectures, Williams said he felt empowered to expand his own capabilities by learning more about the various functions of the Blackboard and Zoom platforms.

“Instead of panicking, I chose to engage this moment as professional development, as I reassessed how I can better leverage online resources in my course instruction,” he said.

Dyson Scholars in Residence

What did remote education look like for the Dyson Scholars in Residence Program (DSIR), established on the Pleasantville campus around the very idea of living and learning together?

According to Associate Professor of English Jane Collins, PhD, DSIR’s program creator and director, the greatest challenge was working out plans to continue a service project for the Successful Learning Center (SLC) (a community program providing a college experience for alternative learners and students with developmental disabilities).

At its final in-person meeting, the DSIR class committed to continuing to serve the SLC students until the end of the semester as planned, and began brainstorming virtual projects and ways to connect via Zoom.

“In our first virtual class together, the SLC students made short films that consisted of monologues, which, when connected together, created a story,” Collins said. “All of it was improvised; the DSIR students took the assignment I gave them and made it work.”

A big part of the ongoing partnership between the Dyson College students and SLC is providing mentorship and friendship, and Collins says she believes that aspect has been retained even in a virtual format.

“Seeing the SLC program participants smile on the screen made me happy, like I did something productive during my day by making someone else’s a little better,” digital cinema and filmmaking major Austin Duffy ’23 said.

Environmental Studies and Science

During mandated stay-at-home restrictions, we all experienced our personal environments perhaps a bit more than we would have liked. Department of Environmental Studies and Science Clinical Associate Professor Michael J. Rubbo, PhD, who taught Habitats of the Hudson Valley, a field-based course, had to find a way to give students the experience they expected.

“I take the students out weekly to visit habitats throughout the region to assess their condition, so going remote presented a challenge,” Rubbo said. “To address this, I held weekly Zoom lectures with the class and created virtual field visits instead of in-person trips.”

He went out alone to various natural locations and created his own videos, which students were assigned to watch and then submit answers to follow-up questions via Blackboard. “I’m no David Attenborough, but when life gives you lemons . . . ,” Rubbo said.

Pace Performing Arts

When the spring 2020 semester began, students taking Pace School of Performing Arts’s Theater of the Oppressed course planned on completing a service-learning project with Falconworks Theater Company, located in the Red Hook neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York.

That changed when Pace went to remote learning and social distancing became the norm. Reginald Flowers, the adjunct professor teaching the class, moved quickly to find an alternative. Working with the Calling Saves Lives initiative, students contacted members of at-risk populations in Red Hook to check in and assess needs. This included asking basic questions about individuals in the household to determine specific risks or concerns during the shelter-at-home period.

The data is delivered to city agencies responsible for intervening on the public’s behalf,” Flowers said. “It also created a rewarding opportunity for the students and contributed to their own well-being by giving them a purpose during this trying period.”

Falconworks ran a similar program following Hurricane Sandy in 2012, and at that time, the class worked with Carlos Menchaca, who was subsequently elected to represent District 38 on the New York City Council in 2013. Menchaca connected Falconworks with community organizer Carlos Jesus (CJ) Calzadilla, who was in the planning stage of the Calling Saves Lives program, Flowers said.